The IPTA Mock Data Challenges

by the The IPTA Collaboration; Data Challenge Working Group Co-Chairs: Jeffrey S. Hazboun, Jonathan Gair.

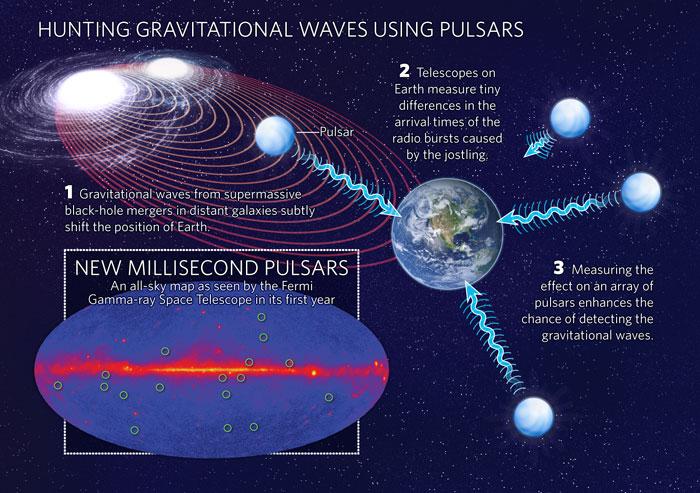

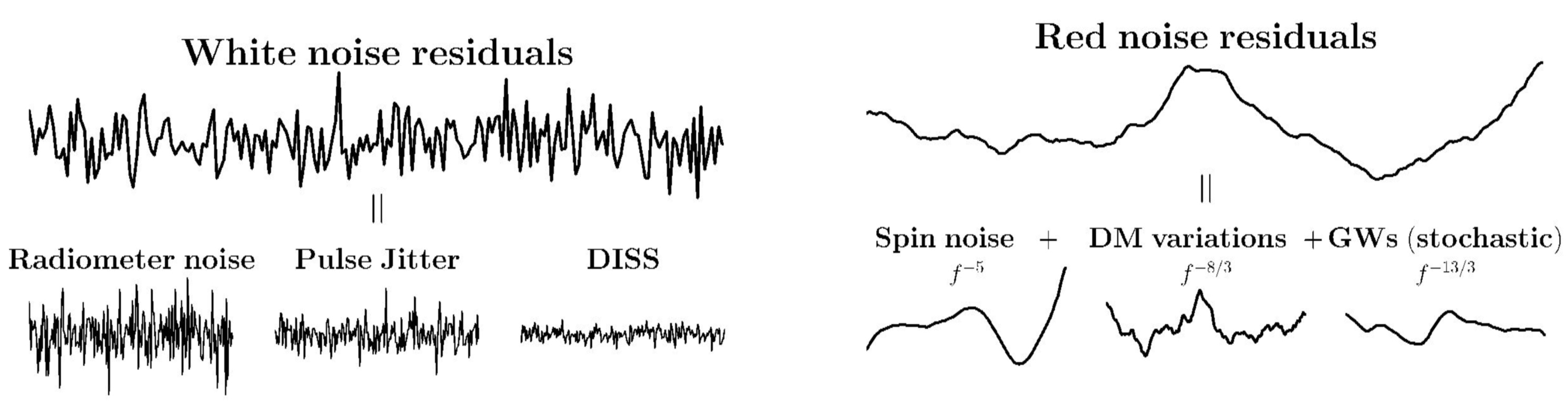

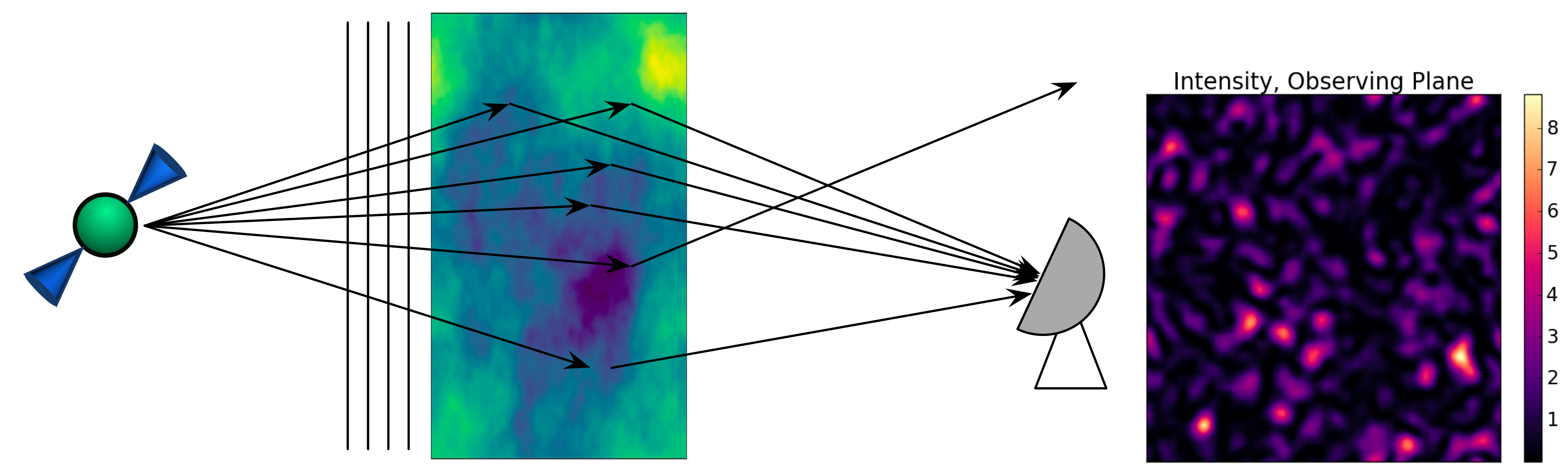

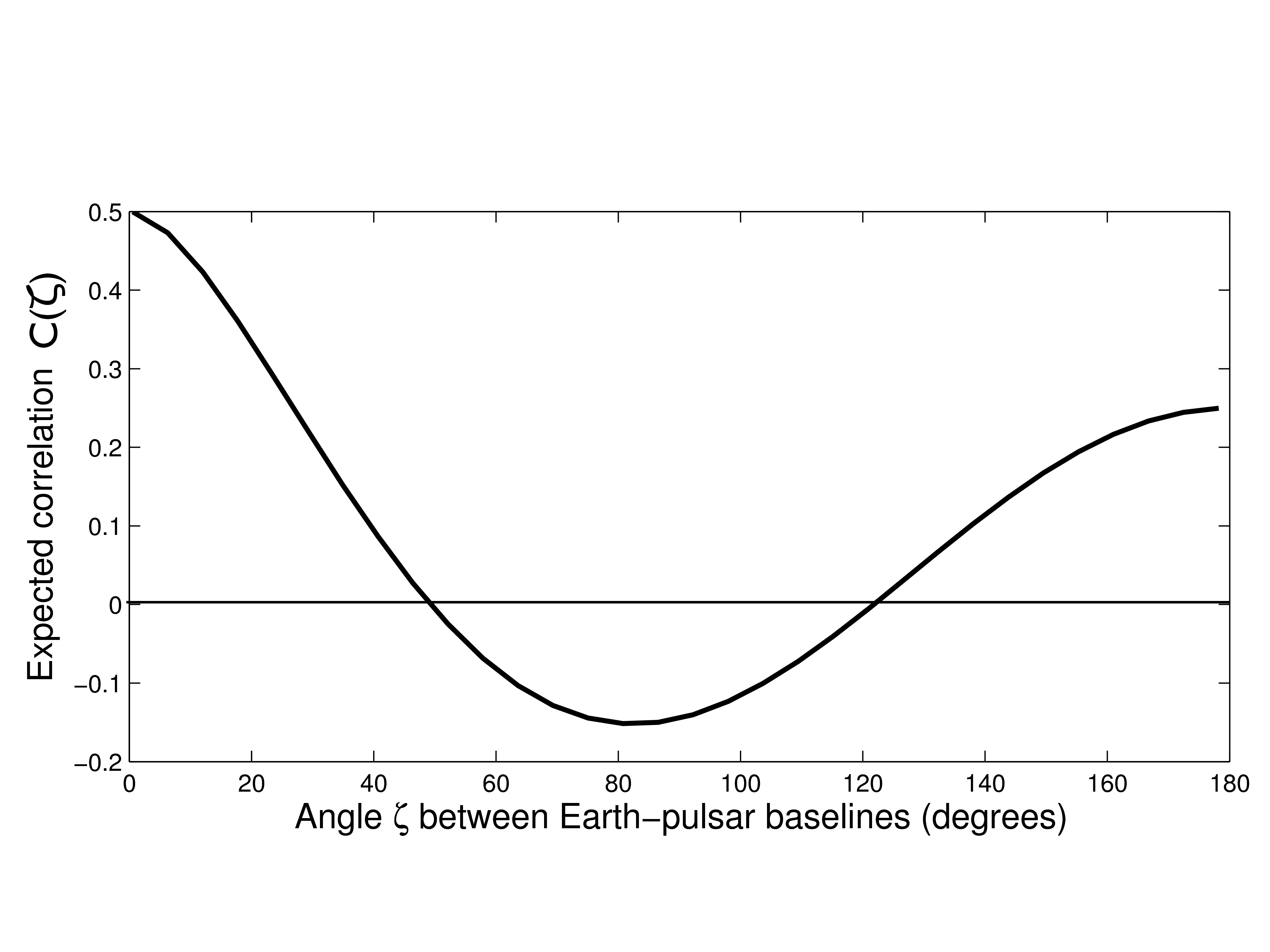

The International Pulsar Timing Array (IPTA) is a galactic-scale gravitational-wave observatory that monitors an array of millisecond pulsars. The timing precision of these pulsars is such that one can measure the correlated changes in pulse arrival times accurately enough to search for the signature of a stochastic gravitational-wave background. As we add more pulsars to the array, and extend the length of our dataset, we are able to observe at ever lower gravitational-wave frequencies. As our dataset matures we are approaching a regime where a detection is expected, and therefore testing current data analysis tools is crucial, as is the development of new tools and techniques. Here we introduce the second IPTA Mock Data Challenge. The purpose of this challenge is to foster the development of detection tools for pulsar timing arrays and to cultivate interaction with the international gravitational-wave community. IPTA mock datasets can be found on the IPTA GitHub page, IPTA MDC.

Participating in an MDC

In order to participate in an MDC just go to the IPTA GitHub page and fork the repository with the MDC you would like to participate in. Also, send an email to the Data Challenge Working Group Co-Chair, Jeffrey S. Hazboun. This will allow us to update participants about new MDC releases and the currently open datasets. The README on the GitHub page will record any announcements made about ongoing MDCs.

All entries for the currently open MDC2 are due by March 15th, 2019.